Mercury Program 1958-1963

The Mercury Seven Astronauts

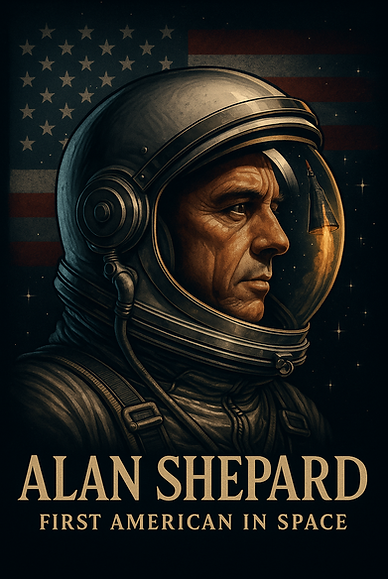

Alan Shepard

Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr. — The Cool-Handed Pioneer

As told by Gideon the Genie

Ah, Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr. — November 18, 1923, East Derry, New Hampshire. Born with the kind of steely calm you normally only find in glaciers and poker champions. Even as a boy, he had that look in his eye that said,

One day, I’m going to leave this planet just to see what’s up there.

I didn’t meet him right away — I tend to drift in and out of decades like you might wander between shops — but trust me, this man was destined for altitude.

Early NASA Career

Fast forward to 1959. NASA’s picking its Mercury Seven — the very first class of astronauts — and I’m loitering near the cafeteria under the guise of “consulting” (read: giving questionable advice in exchange for coffee and the good pencils). In walks Shepard. Navy test pilot. Decorated. Impossibly precise. And dressed like he’d ironed his flight suit inside the cockpit.

He was a perfectionist, yes, but also competitive to the point where you half-expected him to challenge gravity to an arm-wrestle. Dry wit like a scalpel, too. I remember thinking, That one’s going to make history — and look good doing it.

The NASA brass noticed it too. Calm under pressure, disciplined, but with just enough of a mischievous streak to keep things interesting.

Alan Shepard

Alan Shepard

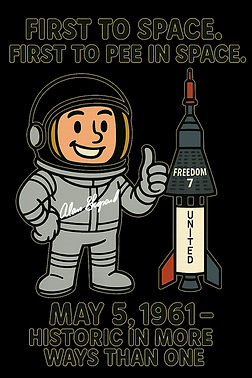

Freedom 7 — and the Longest Bathroom Break in History

May 5, 1961. Shepard’s strapped into Freedom 7 for what was meant to be a quick suborbital hop — just over fifteen minutes in space — short enough you wouldn’t even miss a sitcom episode. Except before they could launch, the weather threw a tantrum, the tech teams fussed, and suddenly he’d been in that capsule for over four hours.

Then came the immortal line over the comms:

“Man, I’ve got to pee.”

The suits on the ground panicked — “Oh no, what if it shorts out the sensors?” — but Shepard wasn’t playing. HE HAD TO GO! Eventually, they let him go. Congratulations, Alan: first American in space and first American to christen a spacesuit.

When the delays dragged on even further, Shepard cut through the chatter with the phrase that’s still quoted at NASA today:

“Why don’t you fix your little problem and light this candle?”

Fifteen minutes later, America had its first human spaceflight, and Shepard had a permanent spot in spaceflight history.

Alan Shepard

Alan Shepard

Alan Shepard

The Long Wait and Apollo 14

In 1964, life threw Shepard a curveball: Ménière’s disease, a condition that scrambled his balance. Most pilots would have hung up the helmet. Not Shepard. He stayed at NASA, training astronauts and shaping missions from the ground.

After corrective surgery in ’69, he was cleared for flight again — and you’d better believe he was gunning for something big.

Our Little “Unscheduled” Encounter

During Apollo 14 simulator training, the room was pure business. Checklists, simulated craters, hushed comm chatter — the kind of environment where fun goes to die. Naturally, I couldn’t resist stirring the pot. So I slipped a single golf tee onto the lunar surface model.

Shepard clocked it immediately. Didn’t smirk, didn’t miss a beat — just glanced at it and said, “Guess I’ll pack my six-iron.”

I figured it was a throwaway line. The kind of dry little quip you forget the next day.

The Follow-Through

Fast forward to 1971. Shepard’s commanding Apollo 14, and he becomes the fifth man to walk on the Moon. Then — I kid you not — he produces a six-iron club head, fits it onto a sample collection tool, and hits two golf balls right there on the lunar surface. Claimed they went “miles and miles.” Physics says 40 yards, tops. But on the Moon? Style points count double.

Anecdotes & Personality

Style Conscious: Flight suits pressed to within an inch of their lives, even during training. Crewmates swore he was secretly angling for a GQ cover.

Competitive Streak: Once tried to break John Glenn’s centrifuge endurance record purely for bragging rights.

Practical Joker: Had a knack for planting gag items in simulators — like a Playboy magazine tucked into a checklist — with himself as the prime suspect.

Alan Shepard

Alan Shepard

Legacy

Shepard was the first American in space and the only Mercury astronaut to walk on the Moon. He bridged the wild west days of early NASA with the glory of Apollo, carrying himself with that signature blend of cool precision and showmanship.

From “light this candle” to Moon golf, he showed the world astronauts could be both consummate professionals and unapologetically human.

On July 21, 1998, in Pebble Beach, California, he took his final bow at age 74, from complications related to leukemia. But listen closely at any launch countdown, and you’ll still hear him — cool, daring, and ready to light the next candle.

Alan Shepard

Alan Shepard

Alan Shepard

Alan Shepard

Alan Shepard

Before becoming an astronaut, Shepard once landed a jet on an aircraft carrier without radio communication after his equipment failed, relying solely on hand signals from the deck crew.

He was the only Mercury astronaut to also command a Moon mission, bridging NASA’s first and third human spaceflight programs.

Shepard was an avid speedboat racer, competing in offshore powerboat events in the 1960s and 70s.

He had a habit of memorizing entire technical manuals for spacecraft systems, impressing engineers by reciting specs and procedures word-for-word during training.

Virgil Ivan “Gus” Grissom — The Straight-Talking Engineer

As told by Gideon the Genie

April 3, 1926 — Mitchell, Indiana. Virgil Ivan Grissom, though no one who valued efficiency ever called him that. To us, he was Gus. Small in stature, big in presence, and as no-nonsense as a hammer.

I first crossed paths with Gus in 1959 when NASA was picking the Mercury Seven. I was floating around the edges of things — the way I do — and here comes this Air Force test pilot, Korean War combat vet, and mechanical engineer all rolled into one. He had the build of a man who fit inside the machines he flew, and the brain of someone who could rebuild them blindfolded.

Gus didn’t waste words. If he told you a spacecraft was safe, it was because he’d taken it apart in his mind twice already and reassembled it better. If he told you it wasn’t safe, you changed it — because the alternative was watching him do it for you.

Liberty Bell 7 — July 21, 1961

Two months after Alan Shepard’s flight, Gus became the second American in space, riding the Mercury-Redstone 4 — Liberty Bell 7 — on a fifteen-minute suborbital hop. The launch was smooth, the flight was flawless, the splashdown… well, that’s where things got interesting.

As he bobbed in the Atlantic waiting for pickup, the hatch blew open without warning. Seawater poured in, the capsule started to sink, and Gus — weighed down by his waterlogged suit — had to swim for his life. A rescue helicopter tried to haul the capsule out, but it was too heavy. Liberty Bell 7 disappeared beneath the waves, 15,000 feet down.

Now… between you and me, I might have been hovering nearby, impatient to congratulate him. I gave the hatch a friendly little knock — just a “Hey, great job, Gus!” — and the next thing I know, BOOM. Hatch gone, seawater rushing in, Gus thrashing like he’s late for shore leave.

For years, people whispered he’d triggered the hatch himself. Gus always said no, and I believe him — partly because the detonation bruised his hand, and partly because I was there, biting my lip and pretending I had nothing to do with it. Decades later, when they recovered the capsule, the analysis proved him right. Gus didn’t need vindication… but he got it all the same.

Gemini 3 — Sandwiches in Space

By ’65, Gus was back in the pilot’s seat, commanding Gemini 3 with John Young as co-pilot. The mission was smooth… right up until Young, the rascal, produced a contraband corned beef sandwich mid-flight.

Now, you should know… I might have been loitering near the simulator a week earlier, chatting with John about the “great culinary injustices of spaceflight.” Purely hypothetical talk, of course. I may have casually mentioned how funny it would be if the first real space meal wasn’t some freeze-dried science project but something truly terrestrial… like a corned beef on rye.

Fast-forward to launch day — John reaches into his suit pocket, and there it is. Gus gives him that “are you kidding me?” look, but takes the sandwich anyway. Zero gravity plus rye bread equals a blizzard of crumbs, so the experiment ended almost immediately.

Gus took the blame with a grin, calling it “the first corned beef in space — and the last.” NASA banned sandwiches after that, but deep down, I know he was proud to have been part of the tastiest mutiny in orbit.

Gemini 3 — Sandwiches in Space

By ’65, Gus was back in the pilot’s seat, commanding Gemini 3 with John Young as co-pilot. The mission was smooth… right up until Young, the rascal, produced a contraband corned beef sandwich mid-flight.

Now, you should know… I might have been loitering near the simulator a week earlier, chatting with John about the “great culinary injustices of spaceflight.” Purely hypothetical talk, of course. I may have casually mentioned how funny it would be if the first real space meal wasn’t some freeze-dried science project but something truly terrestrial… like a corned beef on rye.

Fast-forward to launch day — John reaches into his suit pocket, and there it is. Gus gives him that “are you kidding me?” look, but takes the sandwich anyway. Zero gravity plus rye bread equals a blizzard of crumbs, so the experiment ended almost immediately.

Gus took the blame with a grin, calling it “the first corned beef in space — and the last.” NASA banned sandwiches after that, but deep down, I know he was proud to have been part of the tastiest mutiny in orbit.

Apollo 1 — A Friend Lost

When NASA needed someone to command its first Apollo mission, Gus was the obvious choice. He had the experience, the engineering instincts, and the kind of respect you can’t fake — if Gus signed off on something, you could bet your life on it.

But in the months before the mission, he was frustrated. The Apollo spacecraft was ambitious, yes, but riddled with problems. Electrical glitches. Communication issues. A hatch that took far too long to open. Gus wasn’t shy about it — he even hung a lemon over the capsule simulator during training, a quiet but unmistakable protest. He wanted it fixed, not for his own comfort, but because he understood what was at stake.

January 27, 1967. A routine pre-launch test at Cape Kennedy. I wasn’t in the room — I never go where I’m not welcome — but I was close enough to hear the chatter turn to shouting, then the alarms. The fire spread in seconds. The pure oxygen atmosphere, the wiring, the flammable materials… it all conspired against them.

Gus… Ed White… Roger Chaffee… they never had a chance.

I’ve seen centuries of history, and I’ll tell you — some moments never fade. Losing Gus was like losing a compass. He wasn’t just a pilot — he was a problem-solver, a guardian of his crew, a man who made spacecraft safer simply by demanding better.

NASA changed after that day. Safety became sacred. Design flaws were hunted down and eliminated. Countless lives were saved because of what was learned. But the price was three of the best men I ever knew. And for me… it was the day I lost a friend.

Anecdotes & Personality

Hands-On Engineer: He’d crawl inside mockups with a flashlight, looking for flaws, and usually finding them.

Family Man: Always kept a photo of his wife and kids in his flight suit pocket.

Plain Talker: Told a design team, “You guys are building this thing like you don’t have to fly it.” Silence followed… then changes were made.

Corned Beef Co-Conspirator: Good-naturedly took the heat for that sandwich stunt on Gemini 3.

Legacy

Gus Grissom was the first astronaut to fly twice in space, a Mercury pioneer, a Gemini commander, and the man who was supposed to lead Apollo into its new era. His death — along with Ed and Roger’s — reshaped NASA’s culture forever, making safety the foundation that carried men to the Moon.

April 3, 1926 to January 27, 1967. Forty years on this Earth.

And every one of them counted.

Before becoming an astronaut, Shepard once landed a jet on an aircraft carrier without radio communication after his equipment failed, relying solely on hand signals from the deck crew.

He was the only Mercury astronaut to also command a Moon mission, bridging NASA’s first and third human spaceflight programs.

Shepard was an avid speedboat racer, competing in offshore powerboat events in the 1960s and 70s.

He had a habit of memorizing entire technical manuals for spacecraft systems, impressing engineers by reciting specs and procedures word-for-word during training.

🌎 Friendship 7 – John Glenn’s Historic Orbit (February 20, 1962)

Narrated by Gideon the Genie

"Now this… this is the moment the world held its breath. February 20th, 1962. The day a man climbed inside a capsule called Friendship 7, rode a missile named Atlas, and did what no American had done before: orbited the Earth."

"His name? John Herschel Glenn Jr. Marine Corps pilot, test pilot, war hero, and let me tell you—if the Mercury Seven were a deck of cards, Glenn was the ace. Cool under pressure, polite to a fault, and so squeaky clean you could use his chin to sharpen razors."

“I was right there in the stratosphere, floating beside the capsule, watching history write itself in contrails and courage. He orbited Earth and made the world exhale in relief.”

🛫 The Man with the Right Stuff

"Glenn wasn’t just a pilot. He was the prototype—clean-cut, crew-necked, and cool under pressure. A Marine Corps fighter pilot with over 9,000 hours of flight time, he flew 59 combat missions in World War II, another 90 in Korea, and once chased down a MiG just to make a point. After the wars, he became a test pilot, setting a transcontinental speed record in 1957 during Project Bullet, flying from Los Angeles to New York in under 3.5 hours. He even appeared on Name That Tune. I’m not kidding. He was basically Captain America with a pilot’s license."

🚀 Launch Day: Mercury-Atlas 6

"By the time launch day rolled around, Glenn had already become the face of the space program. NASA knew they were putting America’s hopes, fears, and TV ratings on one man. On February 20, 1962, at 9:47 AM EST, he was strapped into Friendship 7 atop an Atlas LV-3B rocket—a machine that had a reputation for exploding roughly as often as it succeeded. The world held its breath, and then—ignition."

"He reached orbit in just under five minutes. His flight lasted 4 hours, 55 minutes, and 23 seconds—completing three full orbits of the Earth at an average altitude of 160 miles and a speed of over 17,000 miles per hour. And the views? Spectacular. Glenn described watching the sunrise over the Indian Ocean, marveling at the thin blue line of Earth’s atmosphere, and reported seeing what he called ‘fireflies’—tiny, glowing particles drifting around the capsule, which I tried to explain were just frost flakes. He didn’t believe me."

⚠️ The Heat Shield Scare

"But no Mercury mission would be complete without a near-death experience. Halfway through the flight, sensors on the capsule signaled that Friendship 7’s heat shield might be loose. If that was true, re-entry would turn Glenn into stardust. Mission Control, not wanting to take chances, told him to leave the retro-rocket pack attached during re-entry. A makeshift fix using literal explosive hardware to hold the shield in place. Wild? Yes. But it worked."

"He splashed down in the Atlantic, about 800 miles southeast of Cape Canaveral, and was picked up by the USS Noa within minutes. When the hatch was opened, Glenn emerged grinning, alive, and completely unfazed. He had done it. He had orbited the Earth, survived the return, and reminded the world that the U.S. was still very much in the race."

A Hero on Earth—and Beyond

"When he returned home, Glenn was a national hero. He was paraded through the streets of New York, spoke before a joint session of Congress, and even had a ticker-tape shower in his honor. He was the American dream wrapped in a pressure suit. And NASA? They wouldn’t let him fly again. Too valuable. Too iconic. Too… irreplaceable."

"So he turned to politics. Served as a U.S. Senator from Ohio for 24 years, fighting for science funding and space exploration with the same passion he flew with. And just when you thought he’d ridden off into the sunset, he did something that blew even my mind—he came back."

👴🌌 The Oldest Astronaut in Space

"Now, just when you thought John Glenn had hung up his helmet for good—boom! He comes back for one last ride. It’s 1998. NASA’s flying shuttles, cell phones flip open like Star Trek props, and John Glenn? He’s 77 years old, with a chest full of medals and a smile that still made half of Congress feel underqualified."

"They said it was about studying the effects of spaceflight on aging, but let’s be honest—John wanted one more chance to feel the hum of launch under his boots. So they gave him a seat on STS-95, aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery. Launched October 29, 1998. And I was right there, floating just above the cargo bay, watching the old lion rise again."

"He orbited the Earth 134 times over 9 days, conducting medical experiments, strapping on sensors, and proving once and for all that age may wrinkle the skin—but not the spirit. You should’ve seen the rookies on board—wide-eyed twenty-somethings who couldn’t believe they were flying with a living legend. And Glenn? He moved like he never left. Found his rhythm in zero-G, cracked a few jokes, and soaked in the view like an old friend revisiting a childhood home."

"He became a symbol again—not just of Cold War glory, but of timeless purpose. Proof that you never stop exploring, never stop reaching, never stop saying, ‘Yes, I’ll go.’"

"And when he passed in 2016, the flags dropped to half-staff, the headlines echoed his name, and even the stars seemed a little quieter that night. But listen—not all stars burn out. Some of them just go home. And somewhere out there, I like to think John Glenn is still orbiting… still watching… still smiling."

🎖️ Gideon’s Final Word

"John Glenn didn’t just fly missions—he carried a nation’s hopes on his shoulders and brought them safely home. He was the calm in the chaos, the fire in the sky, the man who looked into the void… and waved."